Indiana flubs election security: taxpayers to spend $10+ million on questionable machines

In March, Indiana made what may be seen for years to come as a colossal mistake for election integrity.

With almost no discussion, a bill authored by Rep. Timothy Wesco, R-Osceola, was pushed through the Indiana General Assembly to add a paper audit trail to voting machines that are used in 57 of 92 Indiana counties.

The problem is, the printers that are supposed to add that paper audit trail don’t produce real paper ballots that can be easily counted by hand in a post-election audit or recount.

What they do is print on a roll of narrow, thermal paper that remains inside the machine.

Shockingly, Rep. Wesco, the chairman of the House elections committee, appeared to lie about this in testimony before the Indiana Senate appropriations committee on February 24 — the last committee to hear the bill before it was to go to the full Senate to be voted on, saying “there is a ballot that is printed out that the voter verifies.”

Wesco was refuting testimony from the one citizen who testified that day — Barbara Tully of Indiana Vote by Mail, who told the senators on the committee that no paper comes out of the machine — that the machines do not produce real paper ballots.

A senator questioned Wesco, and he affirmed his testimony, saying “correct,” when the senator asked if the machine prints out a piece of paper that the voter can look at.

Bizarrely, Wesco again reiterated what he’d said in his testimony, that this paper is inserted into another machine. Nothing like this happens with a VVPAT.

This is the chairman of the House Committee on Elections and Apportionment lying to the Senate committee about the equipment that is being proposed to add a paper audit trail to voting machines used in more than half of Indiana counties.

On the basis of Wesco’s false testimony, the committee voted to advance the bill to the full Senate, where it passed a few days later, on March 1.

(To watch the full hearing on Wesco’s bill, with testimony about the voting machines, go HERE.)

The voting machines in question are from an Indianapolis company called MicroVote General Corporation.

They’re used only in two states: Indiana and Tennessee (hmmm….don’t you wonder why other states aren’t using them??)

In Indiana, they’re used in several of the most populous counties in the state, including Lake County, Allen County, Hamilton County, Hendricks County, Boone County, Johnson County, Tippecanoe County, LaPorte County, Delaware County and many others (see full list at bottom).

To vote on a MicroVote machine, you push buttons next to the names of candidates you want to vote for, hit a red button to cast your vote, walk away and hope for the best!

As the machines have been used, there’s no paper record of your vote. Nothing. All they have is the digital record inside the machine.

Experts have been warning for years that these kinds of machines, called DRE machines (for Direct-Recording Electronic), should not be used, as they provide no way to check that the machine count is accurate — no way to verify that the total the machine produces at the end of the day is really an accurate reflection of votes cast.

Heeding these warnings, MicroVote has come up with printers that can attach to the MicroVote Infinity voting panel with a cord. They’re called VVPAT printers, for “voter verifiable paper audit trail.”

These are the devices Wesco was describing inaccurately in his Senate testimony.

As you can see from this MicroVote video below, no paper comes out of the machine that a voter can hold and review. The roll of paper remains inside the machine, and voters are supposed to verify their selections through a clear glass or plastic window.

I have called Rep. Wesco’s office and requested to speak with him about his testimony. He will not return my calls.

I emailed questions to him through his staffer. One of them was: Why did you testify at the Senate appropriations committee hearing that there is a "ballot printed out that the voter verifies" that is "entered into another piece of equipment" when the MicroVote website shows that it is a roll of paper that remains inside the machine and is not printed out? Were you referring to another kind of machine?

His staffer responded that he’d received the questions and would pass them along to Rep. Wesco.

But I never heard from Wesco.

Wesco’s bill, House Bill 1116, which he introduced at the request of Secretary of State Holli Sullivan, moves up the date by which counties have to have VVPATs to July 1 of 2024. The original date was 2029.

The VVPATs are intended to serve two purposes:

To allow the voter to verify their selections before hitting the final button to cast their vote; and

To allow election officials to do a post-election audit, to verify using paper that the machine readout of votes was correct, or a recount, in the event of a close race or legal contest.

But according to many reports, they don’t work well for either of these purposes.

One, it’s been shown that most voters don’t stop and verify that their selections are correct before casting their vote.

Election workers don’t tend to draw the voter’s attention to the small window next to the voting panel, and recommend they check their selections. And even if election workers DO instruct voters to do this, studies show if a different candidate name is printed other than the one they selected, voters often don’t notice it.

But the most concerning question is whether you can really audit an election or do a recount from a roll of thermal paper.

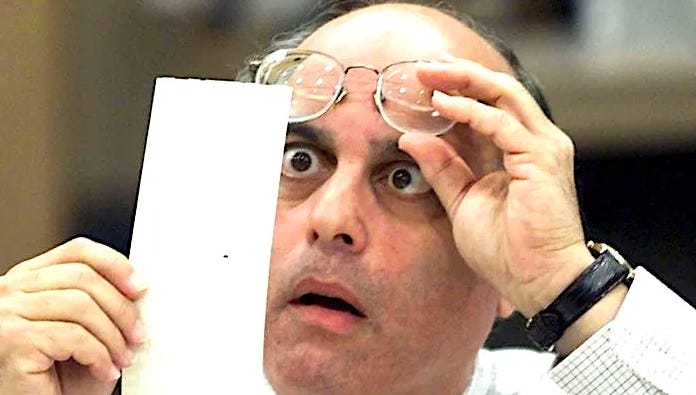

Remember the most famous recount in American history? That iconic photo of the Palm Beach County election worker holding up a punch card ballot to the light?

In this case, with the VVPATs, there is no ballot whatsoever to examine. You have a roll of receipt tape.

In 2007, researchers at Rice University did a study to determine the speed and accuracy doing a hand recount using this roll from a VVPAT printer. Just two races from a spool of 120 ballots were counted. The college students involved in the study had to take a scissors and cut through the tape to separate the ballots, removing the rejected ballots.

“This task was time-consuming and prone to high error rates, with only 57.5% of participants’ counts providing the correct election results,” the report found.

Three people counting just one race on 120 ballots required .74 to .85 work hours, leading the researchers, Stephen N. Goggin and Michael D. Byrne, to remark that a complete recount of a large county such as Cuyahoga County, Ohio (home to Cleveland) with 673,740 voters in the 2004 presidential election would take between 4155 and 4772 hours of labor — so, TWO YEARS for two people to do it! Or ONE YEAR if four people are counting, working every day, Monday through Friday.

“This laborious recounting process strongly suggests that using VVPATs as a check on DRE systems may not be practical,” Goggin and Byrne write.

And why mention Cuyahoga County?

Because in Cuyahoga County in the May 2006 primary, where VVPATs were used with DRE machines, it was found that 10% of VVPAT spools had been destroyed or were blank, illegible or missing and 19% of the VVPAT tapes showed a discrepancy between the tallies.

Ya.

Also in 2006, the Georgia Secretary of State released a report of a pilot project in three counties using VVPATs. It was found that the average time used to audit a single VVPAT ballot was 11 minutes. Based on the project, researchers predicted it would cost $3 per vote cast to do an audit. So a full recount of VVPAT ballots in Cobb County, Georgia, where 179,652 votes were cast in the November 2006 general election would cost more than $500,000!

In 2007, voting machine cybersecurity expert Avi Rubin testified before a congressional committee that after years of study, he’d concluded that DREs with VVPATs were “not a reasonable voting system” as they did not provide election security that can only be achieved with optical scanners — in which a voter marks a ballot by hand and that ballot is then inserted into a scanner.

“Finally, I was asked if I thought that a DRE with a paper trail was an adequate voting system. I replied that when I first studied the Diebold DRE in 2003, I felt that a Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) provided enough assurance. But, I continued, after four years of studying the issue, I now believe that a DRE with a VVPAT is not a reasonable voting system. The only system that I know of that achieves software independence as defined by NIST, is economically viable and readily available is paper ballots with ballot marking machines for accessibility and precinct optical scanners for counting - coupled with random audits. That is how we should be conducting elections in the US, in my opinion.”

- Avi Rubin, professor of computer science, Johns Hopkins University and author of the 2006 book Brave New Ballot: The Battle to Safeguard Democracy in the Age of Electronic Voting, in 2007 testimony before U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Rubin is considered one of a handful of top experts in the United States on electronic voting.

Rubin was a cybersecurity expert working for AT&T when AT&T was hired in 1997 by the government of Costa Rica to design a secure electronic voting system to be used in that country’s next presidential election.

Initially excited by the project, he says he quickly came to realize how easy it would be to fix the election with electronic voting machines.

“What was interesting is I came to the project very enthusiastic, thinking, ‘Now this is going to be the most fun thing I ever built.’ And as we’re working on it and designing it, I kept thinking, ‘You know, if I wanted to build this so that whoever I wanted to win would win, I could do that, and they would never know it,’” Rubin said in a talk while promoting his book Brave New Ballot.

He says he concluded that electronic voting was a “terrible system” and was alarmed in 2003 to find out that electronic voting machines, DRE’s, were already being used in 37 states in the U.S.

Rubin is not the only prominent cybersecurity expert warning against the use of VVPATs.

In 2018, Andrew Appel of Princeton University called VVPATs “an idea whose time has passed” saying the idea of trying to achieve election security with VVPATs was “already obsolete” by the year 2009.

In an article on the website Freedom to Tinker, he warned that states “should not adopt” a voting system combing DREs (like the MicroVote machines) with VVPATs for the following reasons:

The VVPAT is printed in small type on a narrow cash-register tape under glass, difficult for the voter to read.

The voter is not well informed about the purpose of the VVPAT. (For example, in 2016 an instructional video from Buncombe County, NC showed how to use the machine; the VVPAT-under-glass was clearly visible at times, but the narrator didn’t even mention that it was there, let alone explain what it’s for and why it’s important for the voter to look at it.)

It’s not clear to the voter, or to the poll worker, what to do if the VVPAT shows the wrong selections. Yes, the voter can alert the poll worker, the ballot will be voided, and the voter can start afresh. But think about the “threat model.” Suppose the hacked/cheating DRE changes a vote, and prints the changed vote in the VVPAT. If the voter doesn’t notice, then the DRE has successfully stolen a vote, and this theft will survive the recount. If the voter does notice, then the DRE is caught red-handed, except that nothing happens other than the voter tries again (and the DRE doesn’t cheat this time). You might think, if the wrong candidate is printed on the VVPAT then this is strong evidence that the machine is hacked, alarm bells should ring – but what if the voter misremembers what he entered in the touch screen? There’s no way to know whose fault it is.

Voters are not very good at correlating their VVPAT-in-tiny-type-under-glass to the selections they made on the touch screen. They can remember who they selected for president, but do they really remember the name of their selection for county commissioner? And yet, historically in American elections, it’s as often the local and legislative offices where ballot-box-counting (insider) fraud has occurred.

“Continuous-roll” VVPATs, which don’t cut the tape into individual ballots, compromise the secrecy of the ballot. Since any of the political-party-designated poll watchers can see (and write down) what order people vote on the machine, and know the names of all the voters who announce themselves when signing in, they can (during a recount) correlate voters to ballots. (During a 2006 trial in the Superior Court of New Jersey, I was testifying about this issue; Judge Linda Feinberg saw this point immediately, she said it was obvious that continuous-roll VVPATs compromise the secret ballot and should not be acceptable under New Jersey law. )

It might be possible to say that legislators didn’t know about many of these issues with VVPATs that have been identified by top cybersecurity experts, except that they did, because a letter was sent to all members of the Senate appropriations committee prior to their vote to approve Wesco’s bill on February 24. (The same letter was also sent to Secretary of State Holli Sullivan and to the Indiana Clerks Association.)

It’s here:

February 22, 2022

Dear Chairman Mishler and Members of the Senate Appropriations Committee:

As organizations dedicated to supporting voting rights and secure, trustworthy elections, we are writing to urge the Appropriations Committee to reject proposals for implementation of Voter Verified Paper Audit Trails (VVPATs) included in HB 1116. Indiana has wisely recognized the need for voting systems which provide paper ballots to increase security and voter confidence but adopting VVVPATs is the wrong solution. HB 1116 would encourage Indiana counties with obsolete Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machines to patch them with thermal, cash register-style printers that to produce VVPATs by 2024, a move that ignores best practices for security and auditability. VVPAT printers print voters’ choices on small, thermal paper rolls that are difficult to read. But even more problematic, because the thermal paper record is difficult to handle for audits and recounts, the VVPAT system is designed to record votes in QR codes, indecipherable by voters, and to perform audits and recounts from this digital record, not from the human readable text, contrary to all election security best practices. Furthermore, at $2600 per printer, VVPATs represent an exorbitant investment in an election security dead end; throwing good money after bad, which is why it is unlikely they will qualify for federal funding. We expand on these concerns in more detail below.

Why paper ballots matter – and how “VVPATs” miss the point

• Electronic voting systems inherently are vulnerable to errors, bugs and hacking, and because many voters lack confidence in such technology, it is essential to be able to check election results independently.

• Election security best practices dictate that all votes should be recorded on paper ballots that are verified by the voters to ensure their accuracy. These paper ballots should be used in tabulation audits and recounts to check vote counts.1

• Indiana’s VVPATs are installed next to voting machines, and print voter selections on thin, narrow rolls of thermal paper in hard-to-read font.

• Because votes are printed continuously on rolls, anyone with access to the VVPATs and the voter sign-in records potentially can determine how each voter voted, compromising ballot secrecy.

• The paper records appear behind a window that can display a limited number of contests and selections at a time. Voters – especially voters with disabilities – may not be able to read any of their putatively “voter-verified” selections.

• VVPAT rolls are ill-suited for audits and recounts. The lightweight thermal paper is prone to ripping, smudging, and fading.

• In light of these obstacles, the vendor has offered a plan to “audit” the VVPATs by randomly scanning some of the QR codes appended to each voter record.2 This approach defeats the purpose of paper ballots and audits: to check vote counts against voter-verified records of voters’ selections.

• Voters may or may not have verified the text on the VVPATs, but no voter has any means to verify QR codes. Indeed, many voters distrust voting systems which encode vote selections in QR or barcodes.3 This will not improve confidence.

As researchers at the Center for Civic Design sum up:

Although there are still a small number of current voting systems that use this method of creating a verification record, it has fallen out of favor because of the challenges of using the spooled paper in an election audit and the difficulty of reading and verifying the VVPAT through glass (Appel, 2018) as well as its inaccessibility to some voters with disabilities. 4

1 “Securing the Vote,” The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, September 2018. https://www.nap.edu/resource/25120/Securing%20the%20Vote%20ReportHighlights-Federal%20Policy%20Makers.pdf 2 See: https://microvote.com/products.html, “VVPAT Paper Solution,” video which demonstrates the “audit” scanning system Indiana has contracted to purchase from Microvote which “audits” election results by scanning the QR code on each VVPAT record and Microvote Professional Services Contract EDS A27 20-009 which includes purchases of audit scanners. Available at: http://freespeechforpeople.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2019-eds-a27-20-009-microvote-general-vvpat-services-final-9- 11-19.pdf 3 Emery P. Dalesio, “North Carolina allows bar code ballots despite voter outcry,” Associate Press, August 23, 2019. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/nc-state-wire-north-carolina-voting-election-recounts-voting-machinesd2eebfe12cdc4e8c9f9c7465d523198f 4 Whitney Quesenbery, Suzanne Chapman, Christopher Patton, Robert Spreggiaro, Sharon J. Laskowski, “Voter Review and Verification of Ballots: Review of the Literature and Research Approaches,” Center for Civic Design. Available at: https://civicdesign.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Voter-review-and-verification-literature-review-draft-2020-05-27-post.pdf

The VVPAT printers are unlikely to qualify for federal funding.

• Previous purchases of the VVPAT printers were funded by federal grant money, but Indiana cannot count on federal money to pay for additional VVPAT printers.

• Proposed federal legislation that would provide grants to states for the purposes of replacing voting equipment to provide paper ballots expressly prohibits using federal funds for Indiana’s VVPAT style printers because of their failure to provide durable, voter-verified paper ballots.

• The federal appropriations bill, HR 4502, passed by the House Appropriations Committee explicitly bans states from using federal funds for VVPAT printers, with this clause: …for purposes of determining whether a voting system is a qualified voting system, a voter verified paper audit trail receipt generated by a direct-recording electronic voting machine is not a paper ballot. “ 5

Better solutions are available and permitted under Indiana law.

• Indiana law could also be satisfied by providing pre-printed paper ballots marked by the voter either by hand or ballot marking device, a method of voting that is currently in use in 17% of Indiana counties.6

• Pre-printed ballots, marked by hand or assistive technology, provide a durable, verified record of voter intent, which is more secure, more reliable, less costly, and is suitable for conducting audits and recounts.

• For less than the cost of purchasing outdated VVPAT thermal printers, Indiana could have paper ballots and new ballot scanners across the state.

Overblown costs for outdated technology.

• The cost of the added VVPAT printers, with installation and software upgrades is approximately $2600 per device,7 an extraordinary amount by any measure for the modest thermal receipt printer that is supplied by the vendor.

5 HR 4502, Title V, Election Security Grants. Available at: https://appropriations.house.gov/sites/democrats.appropriations.house.gov/files/documents/BILLS-117hr4502rds.pdf 6 “Indiana’s Voting Machines are Vulnerable to Security Issues,” Indiana University Public Policy Institute, October 2020. Available at: https://policyinstitute.iu.edu/doc/indiana-voting-security-brief.pdf 7 See: Microvote Professional Services Contract EDS A27 20-009 which includes purchases of audit scanners. Available at: http://freespeechforpeople.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2019-eds-a27-20-009-microvote-general-vvpat-services-final-9- 11-19.pdf

• The printers are like cash registers, printing a record that is small, difficult to read and likely to fade over time, making it inappropriate as permanent record of voter intent.

VVPATs do not provide a meaningful way to audit elections.

• Indiana has responsibly aimed to adopt Risk-Limiting Audits or post-election audits, which review a selection of paper records to provide a level of confidence that the election outcome is correct.

• The existing plan to conduct “audits” on the the vendor’s VVPATs put forth by the prior Secretary of State fails to adhere to any foundational principles and best practices of post-election audits, let alone to RLA standards.

• Because of the difficulty involved in manually auditing spooled VVPATs, the vendor is selling to Indiana a scanning device that is meant to “audit” the paper VVPATs by randomly scanning the QRs on the printed ballots.8

• The principles of any post-election audit dictate that the audit should be manually conducted on a record of the votes that the voter has verified. Even if voters review the text, voters cannot verify QR codes, making the audit meaningless.

Conclusion

We greatly appreciated efforts by the Elections Division and county clerks to upgrade election systems to provide Hoosier voters with more secure, auditable, transparent, and trustworthy election processes. But, regrettably, the proposed VVPAT system outlined in HB 1116 does not actually achieve these goals. Alternatively, Indiana elections would be much better protected, and Indiana voters better served, by pursuing options to adopt pre-printed paper ballots, marked by hand or by assistive ballot marking device, as are already used in fifteen Indiana counties. We stand ready to offer information to the legislature that would result in more secure, trustworthy, transparent, auditable election systems. Please do not hesitate to reach out to us if you have any questions or if we can be of assistance.

Sincerely,

Susan Greenhalgh, Senior Advisor - Election Security, Free Speech for the People

Barbara Tully, President, Indiana Vote by Mail

Linda Hanson, Co-President and Barbara Schilling, Co-President, Indiana League of Women Voters

Pam Smith, Verified Voting

If you’re still reading, I’ll just say I think it’s likely that Republican senators didn’t take these concerns seriously as they appeared to be coming from liberal-leaning organizations.

Why should the Republican majority listen to liberal groups on the issue of election integrity?

They shouldn’t necessarily. But if they cared about election security, you would think they would listen very closely to what people like Avi Rubin and Andrew Appel — two of the nation’s top election security experts — have been saying for more than a decade now: That the VVPATs are a BAD IDEA and won’t secure the vote. They will make it entirely possible to fix the vote, in a way that no one would ever be able to discover.

Instead, state legislators abdicated their responsibility, and just did what they were told by the Secretary of State, Holli Sullivan.

After Holcomb signed Wesco’s bill into law on March 14, Holli Sullivan celebrated on Twitter:

Here’s the full list of the Indiana counties using MicroVote Infinity voting machines, which are DRE’s — direct-recording electronic devices: