Covid origins: The clue that everyone seemed to miss could lead to solving the mystery

Both the Right and the Left have been influenced by political ideas: The Right that China must of course be to blame; The Left that we should avoid blaming China. What if they're both wrong?

About five years have passed since the SARS-CoV-2 virus first appeared in Wuhan, China, and we still don’t know where it came from and who is responsible for its release.

We don’t have surveillance video or forensic evidence. We don’t have a whistleblower or an admission of guilt. There’s no police interview, deposition or testimony before a grand jury or in a court of law admitting to what happened.

In June, I wrote a piece here on Crossroads Report summarizing some of the evidence that seems to point to the possibility that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, was a bioweapon that was used by the United States to attack China and Iran, a second epicenter of the virus.

Much of this evidence has been highlighted by Ron Unz, the publisher of The Unz Review, but I included more details on the Stuxnet computer worm used to attack Iran’s nuclear program, and also the pro-biowarfare views of two key people in the Trump administration: John Bolton, national security advisor until September 10, 2019, and Robert Kadlec, the head of pandemic preparedness for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Looking back, I saw that I’d missed something Unz had noted — that Jeremy Farrar, a British infectious disease doctor who was, at the time of the Covid-19 epidemic, the director of the Wellcome Trust, the world’s largest private funder of scientific research, wrote in his 2021 book “Spike” that he and other top scientists believed early on that the virus had either been leaked accidentally or was a biowarfare attack — and that he had been advised by his boss, the former head of Britain’s security service, MI5, to use a burner phone and to take the utmost precaution when discussing this latter possibility.

I was curious enough to get Farrar’s book, and recently read it with great interest.

In “Spike,” Farrar mentions the possibility of intentional release not once or twice, but several times, and relates the shock and awe he felt at the implications of such an attack, presumably on China.

Farrar recalls telling his wife that the new virus might be a bioweapon, writing that saying this out loud “felt like a bombshell.”

He went on to say that he felt he was “caught up in one of the most polarized moments in history since the Cold War” and that the suspicion he had that the virus was a bioweapon was “terrifying” and “explosive, if true.”

He wondered if an engineered virus, whether accidentally leaked or intentionally released, “might be the sort of thing countries could go to war over.”

Farrar was having this conversation with his wife in the last week of January, 2020, about two weeks after the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 had been published. He had just come back from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where he was with Richard Hatchette, the head of CEPI (the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) and a White House advisor during the H1N1 virus, and Stephane Bancel, the head of biotech company Moderna. He’d also been speaking to Britain’s chief scientific advisor and also its chief medical advisor and had been in almost constant contact with Eddie Holmes, a British-born virologist and professor at the University of Sydney who Farrar calls “the outstanding evolutionary biologist of his generation.”

In prefacing his comments about the suspicion that the new virus was a bioweapon, he mentioned the “standout molecular feature” of the virus — the furin cleavage site.

“This novel virus, spreading like wildfire, seemed almost designed to enhance human cells,” he wrote, noting that it “seemingly sprang from nowhere.”

His sense of alarm increased on talking to his boss, the chair of the Wellcome Trust, Eliza Manningham-Buller, the former head of Britain’s domestic security agency, MI5.

“When I told Eliza about the suspicions over the origin of the new coronavirus, she advised that everyone involved in the delicate conversations should raise our guard, security-wise,” Farrar writes. “We should use different phones; avoid putting things in emails; and ditch our normal email addresses and phone contacts.”

In his 2023 book about the virus, “Deception: The Great Covid Cover-up,” Sen. Rand Paul wrote that he thought it was China that Farrar feared.

But I agree with Unz that this doesn’t make sense. Farrar starts his book talking about being in an airport on New Year’s Eve, 2019, and sending a text to his “old friend” George Gao, the head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control, to ask him about a report of a new virus he’d just seen.

Farrar continues to talk to scientist friends in China through 2020 and never mentions being hesitant to be open with them, though he surely understood very well that they were closely connected to China’s communist leadership and were likely being monitored by the Chinese Communist Party.

And of course, as the virus emerged in China, it should be fairly obvious that if the virus was a weapon, then China was the intended target, not the attacker. So Farrar would have much more reason to fear he was being spied on by the Americans than the Chinese.

In 2013, Edward Snowden released information that shook U.S. allies in Europe — revealing that the NSA had been spying on German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other unnamed European leaders, which was later confirmed by Danish reports. Surely, the British would have realized that their good friends the Americans may be listening in on their conversations also.

The day after Farrar’s conversation with Manningham-Buller, he emailed the communications tech manager at Wellcome, asking for a second phone with a different number.

“He found me a blank phone in the Wellcome cupboard and left it charging on my desk while I was in a meeting,” he writes. “I didn’t know the term then but I now had a burner phone, which I would use only for this purpose and then get rid of.”

Actually, a burner phone is usually a pre-paid phone that someone buys at a convenience store. The key thing is that the purchaser does not not pay a monthly bill, so there’s no record of who he is. So in all likelihood, the second phone he was given does not qualify as a burner phone as the bill would be paid monthly by his employer, Wellcome, and would be traceable to Wellcome.

Still, it’s indicative of the heightened sense of danger that Farrar felt, and his formerly MI5 boss felt, that they didn’t think he should be using his normal phone to talk about the possibility that this new and virulent SARS virus had escaped from or been released from a lab.

“When I got home, Christiane insisted I rang people close to us, so they would understand what was going on in case something happened to me,” Farrar writes.

He goes on to recount calling his brother and telling him the virus may have been accidentally released and that the British and American intelligence services were involved.

He also called a friend, a professor of anesthesia and intensive care medicine.

“He could hear the fear in my voice and, in turn, it made him nervous,” Farrar writes. “I told him that there were concerns that the virus might be man-made — and that I was letting him know what was going on in case anything happened to me.”

The friend, Tim Cook, said he remembered Farrar talking about the possibility of intentional release, which he calls “a global disaster with implications for war.”

Farrar continued talking with his friend Eddie Holmes, the evolutionary biologist in Sydney.

Holmes was contacted by Kristian Andersen of Scripps Research Institute in California, who said he was bothered by three things about the new virus:

The furin cleavage site, which made the virus more transmissible and more pathogenic and had never before been seen in a coronavirus;

The receptor binding domain, which he described as being a “perfect key” for entering human cells;

The discovery of a scientific paper that described how to manipulate a coronavirus by inserting genetic material in a certain place to modify the spike protein of the original SARS virus, SARS-CoV-1, which had caused the outbreak in 2002/2003.

Holmes and Andersen knew that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had been doing this kind of work on coronaviruses.

Mystery solved!

Well,…not really.

This is where it gets interesting.

Eddie Holmes’ first reaction to what Kristian Andersen had laid out was: “Fuck, this is bad,” according to Farrar’s telling.

Holmes called Farrar and told him what Anderson had said, and Farrar called Anthony Fauci in Washington, D.C., and asked him to speak with Andersen.

“We agreed that a bunch of specialists needed to urgently look into it,” Farrar wrote. “We needed to know if this virus came from nature or was the product of deliberate nurture, followed by either accidental or intentional release from the BSL-4 lab based at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Depending on what the experts thought, Tony added, the FBI and MI5 would need to be told.”

Much of this has come out in hearings before the U.S. House Oversight Committee’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic.

But something important was missed, I believe.

A first conference call of experts was set up to begin to quickly investigate where the virus had come from. This was still at the end of January, 2020, though the exact date is not noted.

The group started with the core three: Jeremy Farrar, Eddie Holmes and Kristian Andersen, who works at Scripps in La Jolla, California, but is originally from Denmark.

They brought in Andrew Rambaut, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, and Bob Garry, a virologist from Tulane University, and also Michael Farzan, Kristian Andersen’s colleague at Scripps.

Farrar’s wife then recommended three others in addition: Marion Koopmans and Ronald Fouchier, both of Erasmus University in the Netherlands, and Christian Drosten, director of a hospital in Berlin.

“Christiane pointed out that a truly international group would scotch any rumbling that this was a conspiratorial Anglo-American stitch-up against China,” Farrar writes.

A strange comment.

For one, who would be grumbling and why would it matter, given the stakes, what anyone’s nationality was? And did adding two Dutch docs and one German really make it an “international group?” There were no Asians, no Africans, no Hispanics. The group didn’t even include any Southern or Eastern Europeans.

As it turned out, the addition of the three recommended by Farrar’s wife — the two Dutch doctors and the one German — took things in a completely different direction.

“There was derision down the line,” says Farrar in describing the first call the panel held.

The biologists, Eddie Holmes said, “didn’t believe a word of it” — referring to the idea that the virus could have been manipulated in a lab and either escaped or was intentionally released.

He said they didn’t believe it could have come from a lab because if someone was engineering a virus, they wouldn’t use some random bat virus in their own lab; they’d use a familiar strain of coronavirus that they knew could infect cells.

In particular, Farrar names Marion Cooperman, Ronald Fouchier (both Dutch) and Christian Drosten (the German) as the three on the call who held this view.

Marion Cooperman had done her PhD on coronaviruses and was a science advisor to the World Health Organization.

She is quoted by Farrar in the book saying: “There was just no close genetic backbone in the literature, despite there being hundreds and hundreds of genomes of SARS-like viruses in the databases. If you are going to make something, why wouldn’t you use one of those to play with?”

The closest relative to this new SARS virus was one that had come from a horseshoe bat. It was a 96 percent match, but the new virus was still different enough that the scientists were divided when it came to what it meant.

“You get insertions like that in viruses all the time,” Marion Cooperman says in the book, talking about the furin cleavage site. “It happens in nature.”

Kristian Andersen answered back that just because it happened in nature did not rule out unnatural origins, “especially as closely related coronaviruses lacked some of the same structural features.”

Following that first call, Eddie Holmes said: “At that point, I was about 80 percent sure this thing had come out of a lab.”

Kristian Andersen was about 60-70 percent sure it had.

“Andrew and Bob were not far behind. I, too, was going to have to be persuaded that things were not as sinister as they seemed,” Farrar wrote.

Another call was set up, for February 1, 2020. This one would include Anthony Fauci of the NIAID and Francis Collins, head of the National Institutes of Health.

In mentioning the inclusion of both of these top American public health agency heads, Farrar says that Fauci and Collins “understood the extreme sensitivity of what was being suggested, given the anti-China rhetoric coming from President Trump and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo” — one of many such comments that indicated that the panel was influenced by the anti-Trump rhetoric that was so dominant in the U.S. and European media at that time and also that they were naive when it came to the Communist leadership in China.

On the Feb. 1 call, Marion Cooperman and the German, Christian Drosten, argued that there “was no need to invoke an unseen hand to cook up this particular virus.”

They said the elements found in this new virus were probably out there in the wild, and that animal viruses were known to cross over into humans or cross over into other animals, and then humans.

Farrar summed up their arguments on that call by writing that they thought “the new virus was more convincingly explained, scientifically, as a natural spillover than a laboratory event.”

After the call, Andrew Rambaut said in an email that while he still found the furin cleavage site “arresting” (it’s unclear if this is the word Rambaut used or if this is Farrar’s word), he was now persuaded that the virus had acquired it “in an intermediate host species” before jumping into humans.

Farrar, after that call, wrote that he was 50-50 on lab leak (or release) vs. natural origin.

After those two initial phone calls, four of them — Kristian Andersen, Eddie Holmes, Andrew Rambaut and Bob Garry — along with W. Ian Lipkin, a Columbia University biologist, formed an investigative team and got to work on what Farrar describes as a “fingertip search” of the medical literature, the research on the new virus and the epidemiological data on the disease that was soon to be known as Covid-19.

Kristian Andersen is quoted in the book on his feeling at the time, saying: “I was battling with the idea that, having raised the alarm, I might end up being the person who proved this new virus came from a lab. And I didn’t necessarily want to be that person, well-known across the world… And I was thinking, how do we even do this? Am I supposed to call the FBI? What burden of proof were we looking for?”

Again, the unwelcome intrusion of personal feeling in what should have been a dispassionate search for the truth — and a sign that these accomplished scientists, at least some of the most important ones in the story, did not have the stomach that was required of them at this moment.

But not wanting to “be that person” and not wanting to blame the CCP, as he said in a Slack message, were not the only reasons Kristian Andersen was shying away from the lab theory.

Andersen went on to author the now-famous “Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2” article that was published in Nature Medicine on March 17, 2020.

Joining him as co-authors were the other four on the investigative team: Holmes, Rambaut, Garry and Lipkin.

In the article, the authors noted the unusual features of the new SARS virus.

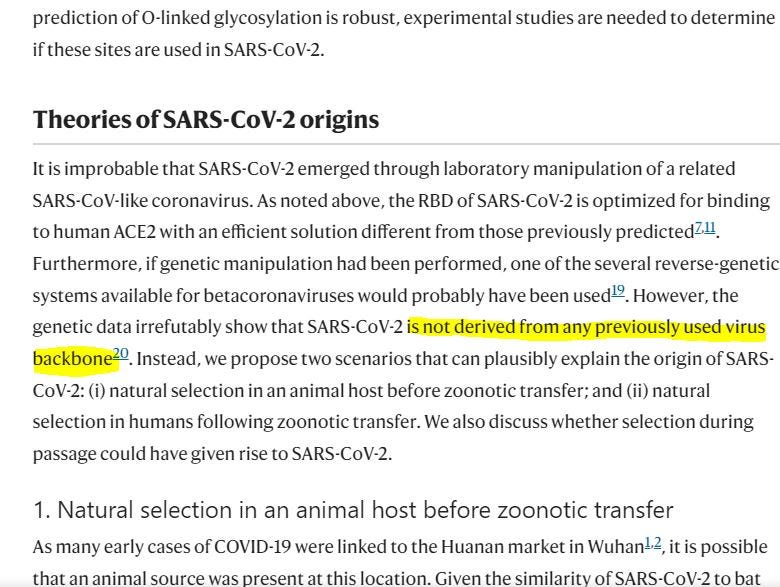

But they gave two reasons for finding that it was “improbable” that the virus had been manipulated in a lab — the first being the receptor binding domain, and the second being that SARS-CoV-2, they said, “is not derived from any previously used virus backbone.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0820-9

In his summary of the paper, Farrar describes it more simply, saying the virus was “unlike any of the known viruses used in gain of function research in labs.”

Kristian Andersen summed it up by saying that scientists are “lazy” and that if they want to make viruses in a lab, they “follow recipes” in use for decades.

“This virus bore no lab signature whatsoever,” Farrar quotes him as saying.

Farrar adds in his own words: “That spoke to Marion’s early observation: why would a scheming scientist not use a known virus?”

There seem to be two obvious answers to this question, and perhaps if the scientists were at their leisure and had had more time to spend pondering it, (and if they were slightly more conspiratorial in their thinking) their minds would have happened upon them.

Why would a scheming scientist not use a known virus?

If he wanted to make sure that no one could trace the virus back to a particular lab.

If he’s had plenty of time to develop a new virus given that he’s working in a government lab — a state-owned lab — that has almost unlimited funding.

The scientists involved in the investigation seemed uninterested in the possibility that the virus may have come out of a lab that doesn’t publish its coronavirus research. These would include the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases — known as the U.S. Army lab at Ft. Detrick in northern Maryland — and Israel’s highly secretive bioweapons lab, the Israel Institute for Biological Research.

Israel’s biological weapons program is so covert that the nation has never made any comment whatsoever about its existence, does not participate in conferences on biological weapons and has repeatedly refused to sign on to the Biological Weapons Convention prohibiting the development of biological weapons. See: https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/israel-biological/

On the U.S. Army lab at Ft. Detrick, it was a scientist there who was fingered by investigators as the most likely perpetrator of the Anthrax attacks that were directed at members of Congress and members of the media shortly after the attacks of 9/11. The Anthrax used in those attacks, sent by envelope, was able to be traced to the Ft. Detrick lab presumably because it was known that scientists there were working with Anthrax. But given this early publication of the “Proximal Origin” article in March of 2020, directing the narrative toward natural origin, and on the other side, the Right wing fixation on China and the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the possibility of the virus having coming out of Ft. Detrick was never even considered by the American media or by congressional investigators.

It seems unlikely that the national security apparatus in the United States will allow an investigation that would shine a light on its own defense laboratory as a possible origin of SARS-CoV-2 or that Israel would countenance its own bioweapons lab being scrutinized. But we could hope that someday, serious researchers may follow this course of investigation to see if there isn’t something there.

Or maybe, years from now, there will be a deathbed confession.

Wouldn’t it be nice to know sooner though?

Thanks for the excellent write-up on corruption at the highest yet unknown level. I will add that a very well-connected, let's call insider, has proof that the virus was known before its release. The WEF head called well-known wealthy individuals and advised them to go all cash; bonds were not even acceptable to hold in the financial markets, only cash. This warning from Schwab triggered the market crash in March. The market recovered quicker than usual, indicating that this was a manipulated drop.

Everything related to covid19 was not natural. Undoubtedly, we were scammed, and as you wrote, hopefully we get more proof.

Excellent article with great incite. I do seem to recall early on Jeremy Farrar's comments getting out early during the pandemic. And it also seams to be a bit of a head scratcher to see Jeremy Farrar communicating about his concerns of a lab leaked/lab produced "virus" causing the pandemic, and Fauci and Collins both being included in conferences, while they were two people being challenged and alleged by Ran Paul, as being involved and contributing to the gain of function and the cause of Farrar's allegations/concerns (evidence of their email exchange). I am please to see so many in the comments acknowledging Terrain theory vs Germ theory (Dr Cowan, Dr Sam & Mark Bailey). It would make much for sense to have created a toxin/poison in the lab, by synthesizing a protein, "perhaps" built off the chassis of a Coronavirus et al, and to assist entering the cell with the SV40 promoter and plasmids with DNA in the vials (Kevin McKernan). So invent the scare (kill a few people in the hospital to sell the scare) and promote the cure and inject the Spike through the cure. And to see it run by DoD/DARPA et al? And all the players in the article are without knowledge, but questioned it, and still fell in line out of fear... And I do not necessarily blame them. Oh but the IRONY....